A History of Banking: France

- Nature and Ideas

- Dec 12, 2024

- 9 min read

Updated: Dec 15, 2024

The French Jews faced social prejudices but enjoyed relative security until the time of the Crusades. They were engaged in financial activities such as the exchange and transfer of money with a degree of immunity.¹ They experienced intermittent persecutions that were generally short-lived. In 1182, Philip Augustus, King of France from 1180 to 1223, ordered their banishment from his kingdom.² He allowed them to sell or take their belongings but confiscated their lands. The king was convinced that there were too many Jews in his kingdom and that they were accumulating great wealth. They faced accusations such as keeping Christian servants and driving these servants away from their true faith. They were also accused of corrupting nobles and commoners and taking their goods after lending them large sums of money.³

Philip the Fair, King of France from 1285 to 1314, tolerated the Jews and appreciated moneylenders for their value to the economy. In 1288, he gave them protection from arbitrary imprisonment.⁴ He later changed his policy and in 1306 ordered all the Jews in his kingdom to be arrested. He then ordered the confiscation of their property and their banishment from his kingdom.

In 1315, Louis X invited the Jews to return to France and gave them back their houses and synagogues.⁵ He permitted them to recover their debt on the condition that two-thirds of the recovered amount be handed to the king. The persecution of the Jews continued during the following reigns. Many of these persecutions, especially by those indebted to the Jews, were based on absurd charges. The Templars, like the Jews, were also targeted because of the immense wealth that they acquired from the money exchange business.⁶

In 1361, the Duke of Normandy, who later ruled France as Charles V, convinced his father John the Good to permit the Jews to conduct their business in France for a period of 20 years.⁷ He argued that they could be a great source of taxes and could also help facilitate monetary circulation and industrial activity. However, their persecution renewed after the death of Charles V. The Jews and the Lombards were even robbed and murdered during the reign of Charles VI (1380 to 1422).⁸

Jacques Coeur

In around 1427, Jacques Coeur, the son of a furrier from Bourges, became assistant to the Mint-Master of Bourges. He was later implicated in a case related to the issuance of coins that did not meet the legal standard. Coeur carefully studied the nature of money and adopted the successful business practices of the Italian republics.⁹ He established branch houses across the Mediterranean shores, gained permission to trade with “infidels” and quickly became one of Europe’s wealthiest merchants and shipowners.¹⁰

In 1435, Coeur returned to Bourges and became the Mint-Master for both Bourges and Paris. He later became the King's Treasurer, which helped him to get a monopoly on money-changing. He lent huge sums to King Charles VII and helped him with the resources that enabled him to drive the English out of France and end the Hundred Years’ War.¹¹ Coeur’s banking operations revolved around the exchange of foreign currencies, especially the purchase of copper and silver coins, which he traded for gold in Egypt.

Coeur was later accused of poisoning Agnes Sorel, Charles VII’s mistress, who died in childbirth. Coeur faced trial and was sentenced to death. But Charles VII, remembering Coeur’s past services, commuted the sentence to life imprisonment. He later escaped with the help of one of his former clerks and went to Rome. He died in 1456.¹² Louis XI later ordered the case against Coeur to be re-examined and cleared him of the charge of poisoning Agnes Sorel.

The Italian bankers, who had a better understanding of finance and credit than the French ministers, were well-received in France and even given important positions to fill.¹³ These Italian financiers, who conceived the idea of farming out dues, later gained great powers as revenue farmers, whose main business was to collect taxes.

The Discount Bank

The Discount Bank or La Caisse d'Escompte was established on January 1, 1767, with a fixed capital of 60,000,000 livres. The bank had a monopoly on the coinage and was authorised to discount commercial paper and state securities. The bank never became fully functional and was abolished in March 1769.¹⁴

Another bank, also named the Discount Bank, was established after a decree issued on March 24, 1776. The bank was authorised to discount any commercial paper accepted by the bank’s directors at a rate not exceeding 4% per annum. It was also allowed to take deposits, payout public funds, and deal in gold and silver. The bank was prohibited from borrowing money at interest or incurring any debt not payable on demand. Additionally, it was explicitly banned from participating in commercial ventures, maritime activities or entering any insurance contracts.

In 1783, the Comptroller-General of Finance secretly borrowed 6,000,000 livres from the bank, which increased the money supply. Once the public discovered the loan, panic ensued, leading to a demand for the redemption of bills and withdrawal of deposits. The bank was unable to meet its financial obligations, forcing the Government to interfere and issue a decree to explain the matter. Following these events, the bank increased its capital to 15,000,000 livres, creating 1,000 new shares of 3000 livres each.¹⁵

In February 1787, the bank issued more shares and changed rules concerning discounts on paper. Under this arrangement, the bank paid 70,000,000 livres to the treasury at an interest of 5%. The interest was supposed to be paid from the government revenues. This amount was a guarantee for the notes in circulation, which amounted to 98,000,000 livres. In a sense, it offered seriously impaired credit as security to its depositors and note-holders and essentially placed its entire capital in the hands of the government. Because of this, the bank got involved in the declining public finances, causing a bank run as early as August 1787. It paid out 33,000,000 livres to the bill holders seeking their redemption.¹⁶ The government intervened, making notes legal tender. The bank’s administrative council opposed the decree and demanded the State return its 70,000,000 livres to meet its current demands. The government handed all the money from its collection bureaus, but could not return the 70,000,000 livres because that sum was already used up.

The Revolution in France - Assignats and mandats territorians

During another panic in August 1788, the bank’s cash reserve was reduced to 25,000,000 livres. The Treasury was now in a bad state. Jacques Necker, the Controller-General, proposed raising a loan of 15,000,000 livres, which was subsequently made against the personal pledge of the King and bills guaranteed by Treasury bonds. In January 1789, the stockholders decided that the bank should lend another sum of 25,000,000 livres to the King. Mirabeau attacked the bank in a pamphlet distributed to his colleagues in September 1789.¹⁷ Necker later proposed to convert the bank into a national bank and increase its capital. He authorised the bank to issue 240,000,000 livres in bills guaranteed by the State. He also proposed to keep it under the supervision of commissioners chosen by the National Assembly. Talleyrand, Bishop of Autun, rejected the idea of converting the Discount Bank into a national bank and instead suggested that the State should return its loans at a rate of 10% per annum.

The National Assembly approved a plan under which the Discount Bank would lend the Government 80 million livres in exchange for the Government’s commitment to sell church lands worth 400 million livres to settle its debts. The decrees of December 19 and 21, 1789, authorized the issuance of assignats, a form of paper currency backed by the lands of the clergy. These assignats were made legal tender.¹⁸ The government was allowed to repay the bank advances made to the Treasury using these new notes. However, the state kept borrowing more money from the bank, causing its eventual downfall.

Deeply concerned with the scarcity of money, the National Assembly ordered the sale of 400 million francs’ worth of ecclesiastical and crown properties. In September 1789, they proposed creating a special Treasury Department to issue assignats, bearing an interest of 5%. This interest rate was reduced to 3% on April 15, 1790. The assignats were made legal tender for transactions between individuals. They were to be accepted by all public departments as the equivalent of coins or specie.

These notes, which were essentially mortgage bonds, depreciated day by day due to their extravagant frequency. During the revolutionary period, forcible means were employed to prevent the depreciation of the assignats. Their depreciation continued and merchants refused to sell their goods at former prices. The capitalists and state creditors were compelled to accept the assignats, a fictitious form of money, at its nominal value. Even the working people were impacted by the defective monetary system as they were not able to buy the actual necessities of life due to rising prices.

By early 1794, the total assignats issued aggregated to nearly 8 billion francs. About 2.46 billion francs of this amount came back to the Treasury and was destroyed.¹⁹ Despite this, the Convention decided to issue an additional 1 billion francs in denominations of 10 sous to 100 francs, raising the net total to approximately 5.54 billion francs. The Convention later attempted to increase the value of paper money by reducing the quantity. By February 19, 1796, the issuance of assignats reached an astonishing 45.5 billion francs. This figure did not include the counterfeit assignats produced by England on the Island of Jersey. The republic later began issuing mandats territorians, or land warrants. It was a new kind of paper money with a total issue amounting to 2,400,000,000 francs. This form of money was essentially a mortgage against public lands and was withdrawn from circulation on March 21, 1797, after its value depreciated and the warrants lost 90% of their value.²⁰

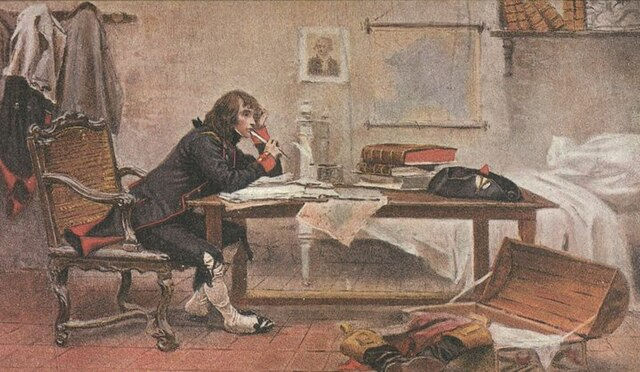

Le Petit Caporal

Napoleon Bonaparte became the First Consul after the Coup of the 18th Brumaire (or November 9, 1799), which replaced the Directory with the French Consulate. Napoleon introspected on the financial condition of France and personally devoted a lot of time studying the mechanism of banking. The idea of the Bank of France was put forward in 1796 and Napoleon discussed the possibility of the bank with the men who contributed to the idea of founding a national bank earlier. He edited the preface of the bank’s constitution with his own hand.²¹

The preface states that in other countries banks played a great role in mitigating the evils associated with the “disorganisation and scattering of capital” and “the derangement of public credit”. These establishments also helped these countries secure “great financial resources”.²⁵

The bank was authorised to discount bills of exchange and draft, collect money for private citizens and public establishments, receive cash deposits, honour cheques and drafts drawn upon the bank, issue notes, and open an investment and savings department. The limit of the issuance of currency was left to the intelligence of the management and the bank was expected to always be in a condition to honour its obligations. The bank's capital was fixed at 30,000,000 francs, divided into 30,000 shares valued at 1,000 francs each.²² These shares were available for subscription at the start of 1800. Napoleon took 100 shares and also made his family members and other people attached to him subscribe for stock. In 1803, Napoleon made the Bank of France the only bank of issue in France. This decision involved raising its capital to 45,000,000 francs and extending its charter until 1818. In 1806, the bank was placed under state control.

On September 24, 1805, the bank faced a significant financial crisis. It owed 61 million francs in notes and 7 million francs in open accounts, but possessed only 782,000 francs in actual cash. The bank stopped payment and resumed it on January 26 1806 after utilising its credit to buy coins from other countries and the Treasury.²³ Following these events, the Government tightened its hold on the bank administration and the bank’s capital was increased to 90 million francs.

The Revolution of 1848

During the revolution of 1848, the bank faced the twin crisis of high demands for discounts and deposit withdrawals. The government intervened by making the bills of the Bank of France and other Departmental banks legal tender and required individuals and public officials to receive them as legal money.²⁴ To bring uniformity in the paper currency, the local banks were consolidated with the Bank of France, which took the assets and liabilities of nine banks. These banks were designated as branches and their shareholders were given an equal number of shares of the Bank of France. This gave the bank a complete monopoly on issuing notes in France. The bank supplied vast sums of money during the early years of the Second Empire for the construction of the railway, government loans and the Crimean War.

The Chambre de Compensation des Banquiers de Paris or the Clearing-House of the Paris Banks was created in 1872.

Nature and Ideas YouTube video on banking in France and Spain:

References:

Dunbar, Charles F. (1900). Chapters on the Theory and History of Banking. G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Essars, Pierre Des (1896). A History of Banking in All the Leading Nations Volume III: A History of Banking in the Latin Nations. The Journal of Commerce and Commercial Bulletin.

Notes:

1 ^Essars, 1896, p. 2

2 ^Essars, 1896, p. 2

3 ^Essars, 1896, p. 2

4 ^Essars, 1896, p. 2

5 ^Essars, 1896, p. 3

6 ^Essars, 1896, p. 3

7 ^Essars, 1896, p. 3

8 ^Essars, 1896, p. 3

9 ^Essars, 1896, p. 4

10 ^Essars, 1896, p. 4

11 ^Essars, 1896, p. 4

12 ^Essars, 1896, p. 5

13 ^Essars, 1896, p. 5

14 ^Essars, 1896, p. 31-32

15 ^Essars, 1896, p. 33-34

16 ^Essars, 1896, p. 36

17 ^Essars, 1896, p. 36-37

18 ^Essars, 1896, p. 39-40

19 ^Essars, 1896, p. 44

20 ^Essars, 1896, p. 46

21 ^Essars, 1896, p. 55

22 ^Essars, 1896, p. 56

23 ^Essars, 1896, p. 59

24 ^Dunbar, 1900, p. 64-65

25 ^Essars, 1896, p, 55

Comments